Beyond the Comfort of Agreement: Why Forced Ranking Reveals More About Cultural Evolution Than Likert Scales

Jun 12, 2025

In co-creating the Adaptive Cultures diagnostic, we set the intention of creating a diagnostic that would assess the stage of cultural evolution and provide insights to help the culture evolve over time.

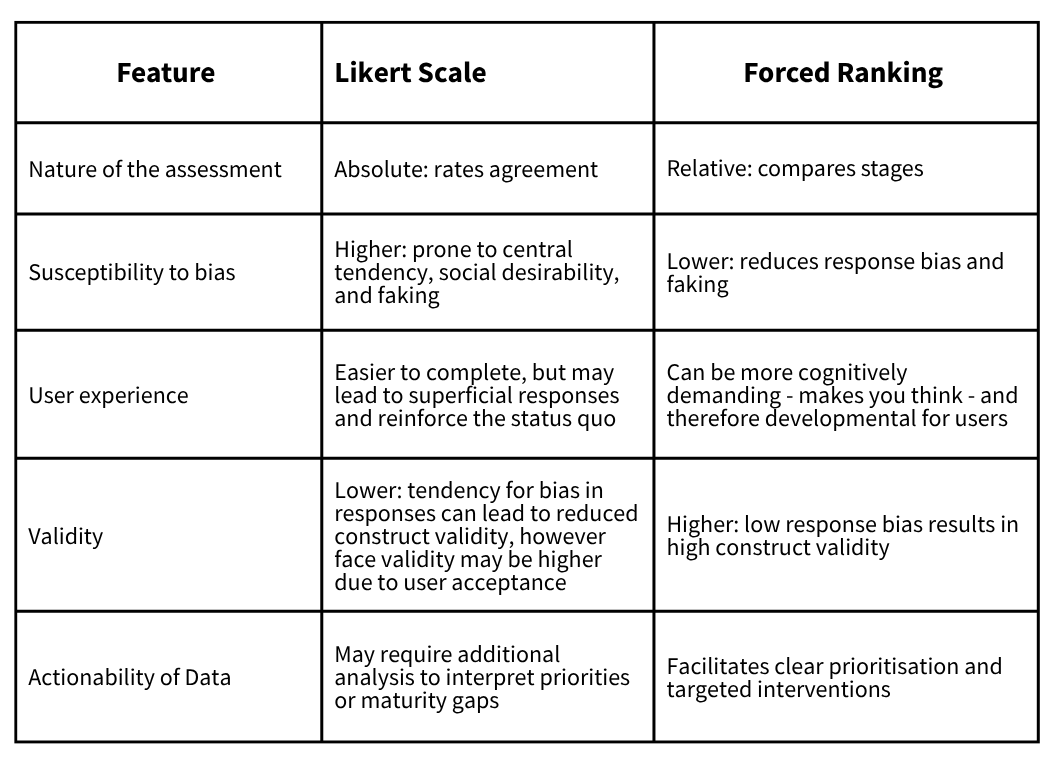

When choosing the most appropriate methodology to measure stages of cultural evolution, we considered two common approaches to surveys — the Likert scale and forced ranking — and contrasted and compared their utility across a range of factors.

In this article, we explain why we chose the forced ranking approach and how such an approach enables a deeper, more nuanced approach to cultural transformation.

From good or bad to continual evolution

Many culture surveys are based on a world view of "good" or "bad" culture, leadership behaviours, or one size fits all. The world view that underpins the Adaptive Cultures diagnostic is one of whole living systems and the evolutionary potential of human beings and systems. It gathers insights into aspects of an organisation's culture which enable adaptation and evolution and aspects which can inhibit these. What may be a strength at one stage of cultural evolution, may actually be a limitation at another. Using a relative scale recognises context and shifts from a right or wrong paradigm. For many users this is wonderful, and for many users this is deeply discomforting or doesn’t provide an opportunity to “Rate the organisation”

The methodology we choose to gather these insights matters more than we might initially imagine. The familiar comfort of the Likert scale—with its reassuring agreement ratings from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree"—may actually obscure the very patterns we're seeking to understand.

The seductive simplicity of agreement

Likert scales feel intuitive. They mirror how we often think about preferences and opinions in everyday life. "How much do you agree with this statement?" seems like a straightforward question. For HR and OD professionals, they offer the additional comfort of familiarity—most people know how to respond, and the data appears clean and quantifiable.

However, when assessing cultural maturity and evolution, this apparent simplicity becomes a limitation. Cultural development isn't about absolute agreement with isolated statements.

Consider what happens when we ask someone to rate their agreement with statements like "We have strong collaborative processes" and "We demonstrate individual accountability." In a Likert format, many respondents will rate both highly, even when these represent different stages of cultural evolution or when one significantly outweighs the other in their lived experience. The result? A flattened picture that tells us little about where the organisation stands in its evolutionary journey.

The revealing discomfort of choice

Forced ranking, by contrast, creates what we might call "productive discomfort." When we ask people to choose which stage of cultural development most accurately reflects their current experience, even when multiple options feel partially true, we surface the relative patterns that matter most for understanding where energy and attention need to be focused.

This discomfort serves a deeper purpose. Cultural evolution requires us to acknowledge where we are, not where we wish we were or where we think we should be. The research consistently shows that forced ranking formats reduce the response biases that can mask these realities—central tendency bias (avoiding extremes), social desirability bias (presenting oneself favourably), and acquiescence bias (agreeing with statements regardless of content).

More significantly, forced ranking reveals the trade-offs that organisations are actually making. When someone must choose between "We prioritise getting things done efficiently" and "We prioritise learning from mistakes and adapting our approach," they surface which mindset truly drives behaviour when these values come into tension, as they inevitably do in real organisational life.

Beyond measurement to transformation

The choice between Likert scales and forced ranking isn't merely methodological; it reflects different assumptions about the nature of cultural development itself. Likert scales tend to reinforce the idea that culture can be improved by accumulating more "good" attributes—better communication, higher engagement, stronger collaboration. This additive approach often leads to what we might call "cultural improvement fatigue," where organisations pursue multiple initiatives without understanding how these elements integrate or which capabilities need to develop first.

Forced ranking, particularly when applied to developmental stages, acknowledges that cultural evolution is more like growing up than accumulating possessions. A teenager isn't an improved child who has added more skills; they represent a qualitatively different stage of human development with its own capacities and challenges. Similarly, an interdependent culture isn't simply an independent culture with better teamwork—it operates from fundamentally different assumptions about decision-making, accountability, and purpose.

The paradox of difficulty and insight

We've observed an interesting paradox in our work: the approaches that initially feel more difficult for respondents often yield the most transformative insights for organisations. The cognitive demand of forced ranking—requiring people to truly consider and compare their experiences—creates deeper reflection than the almost automatic response pattern that Likert scales can encourage.

This deeper engagement serves the broader purpose of cultural evolution. If culture change requires people to examine their assumptions and consider new possibilities, then our diagnostic process should model this kind of thoughtful inquiry. The process of completing a well-designed forced ranking assessment becomes part of the cultural development journey itself.

Questions that guide rather than measure

Perhaps most importantly, forced ranking enables us to ask different kinds of questions—questions that guide development rather than simply measure current states. Instead of "How much do you agree that we have psychological safety?" we might ask people to consider scenarios that reveal which stage of psychological safety most accurately reflects their experience: one focused on politeness and avoiding conflict, one oriented toward honest feedback within established relationships, or one that embraces productive disagreement in service of shared purpose.

These comparative questions don't just gather data; they expand people's understanding of what's possible. They help individuals and teams recognize that what they might have considered "good enough" represents one stage in a longer developmental journey.

Embracing the complexity of evolution

As culture practitioners, we invite you to reflect on how your choice of methodology either supports or limits the cultural development you're seeking to foster. While Likert scales will always have their place for certain types of feedback, assessment of cultural maturity and evolution calls for approaches that honour the complexity and interconnectedness of human systems.

The path forward isn't about abandoning familiar tools entirely but rather expanding our methodological repertoire to match the sophistication of the cultural challenges we're addressing. Just as we encourage organisations to move beyond simplistic solutions to embrace the nuanced work of cultural evolution, we might also need to move beyond the comfort of agreement ratings to embrace the more revealing—and ultimately more useful—insights that come from comparative choice.

Cultural evolution, after all, is fundamentally about developing our collective capacity to make wiser choices in service of our deepest aspirations. Perhaps it's time our diagnostic approaches reflected this same commitment to choice, discernment, and growth.

Selected Bibliography*

- Brown, A., Inceoglu, I., & Lin, Y. (2017). Preventing Rater Biases in 360-Degree Feedback by Forcing Choice. Organizational Research Methods, 20, 121 - 148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428116668036.

- Combrinck, C. (2024). Not Liking the Likert? A Rasch Analysis of Forced-choice Format and Usefulness in Survey Design. SAGE Open, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241295501 (Original work published 2024)

- Goldminz, I (2018). The Likert scale is killing your developmental feedback. Medium. https://orghacking.com/the-likert-scale-is-killing-your-developmental-feedback-4e075875e27a

- Harzing, A., Baldueza, J., Barner‐Rasmussen, W., Barzantny, C., Canabal, A., Davila, A., Espejo, A., Ferreira, R., Giroud, A., Koester, K., Liang, Y., Mockaitis, A., Morley, M., Myloni, B., Odusanya, J., O'Sullivan, S., Palaniappan, A., Prochno, P., Choudhury, S., Saka‐Helmhout, A., Siengthai, S., Viswat, L., Soydaş, A., & Zander, L. (2009). Rating versus ranking: What is the best way to reduce response and language bias in cross-national research?. International Business Review, 18, 417-432. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IBUSREV.2009.03.001.

- Sankaran S, Derechin J, Christakis NA. CurmElo: The theory and practice of a forced-choice approach to producing preference rankings. PLoS One. 2021 May 27;16(5):e0252145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252145. PMID: 34043666; PMCID: PMC8158949.

- Zhang, Bo & Luo, Jing & Li, Jian. (2023). Moving Beyond Likert and Traditional Forced-Choice Scales: A Comprehensive Investigation of the Graded Forced-Choice Format. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 59. 10.1080/00273171.2023.2235682.

*Research for this article was supported by Perplexity and Consensus Gen AI platforms

Our Adaptive Cultures Community

Our Global Community is an enriching space for culture practitioners to share, learn from, explore and develop emerging practices in support of their clients developing needs. On our community platform we share methods and tools, ask questions, conduct developmental conversations and learn together.

Read the Adaptive

Organisations Whitepaper

Download our Adaptive Organisations Whitepaper and learn how to evolve through change and complexity. To receive a copy, please fill in your details below and a copy will be emailed to you.